Designing for Tomorrow: Why Product Lifespan Matters More Than Ever

Content for Designing for Tomorrow: Why Product Lifespan Matters More Than Ever could not be generated.

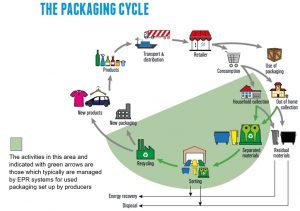

In a world increasingly burdened by waste, the conversation around sustainability is shifting. It’s no longer just about managing disposal—it’s about rethinking how we build products from the start. Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) is emerging as a key driver in this transformation, encouraging companies to prioritize durability and repairability. Rather than simply planning for end-of-life, EPR frameworks now reward those who design products that last longer, work better, and generate less waste over time.

From Fast to Future-Proof: Rethinking Product Design Under EPR

The traditional approach to product design has often prioritized speed, cost-efficiency, and aesthetics over longevity. Products were frequently engineered with planned obsolescence in mind—built to function just long enough to outlast the warranty, but not much longer. However, the rise of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) is reshaping this paradigm. By making producers accountable for their products even after they’re discarded, EPR compels businesses to rethink their entire design strategy—from material selection to end-of-life recovery.

Under EPR, producers are not only responsible for collecting and recycling waste but are also evaluated based on how easily their products can be reused, repaired, or repurposed. This shift has encouraged forward-thinking manufacturers to develop more robust, sustainable design principles. Durability and ease of disassembly are no longer just idealistic goals—they’re fast becoming regulatory expectations and competitive advantages.

For example, India’s E-Waste (Management) Rules require producers to meet collection targets and submit EPR plans, but the compliance process also indirectly pushes companies to reduce waste generation at the source. Products that break easily or are difficult to repair tend to inflate a company’s waste burden, making it harder and costlier to meet compliance targets. As a result, companies are shifting toward ‘future-proof’ designs—those that stay functional longer, can be easily refurbished, or have components that are recyclable.

This design evolution is especially visible in sectors like electronics, automotive, and even consumer packaging, where materials and configurations are being re-engineered for resilience. Beyond regulatory pressures, there’s growing consumer demand for longer-lasting, higher-quality goods. Brands that deliver on this expectation are not only reducing their environmental impact but also building customer loyalty and saving costs over time.

- Designing with disassembly in mind allows for easier recycling and repairs.

- Choosing high-quality, recyclable materials extends product life and recovery value.

- Simplifying product architecture reduces failure points and facilitates maintenance.

Ultimately, future-proofing design under EPR is about creating a closed-loop system where materials and products flow efficiently back into use, not waste. It’s a strategic realignment that benefits businesses, consumers, and the planet alike. As EPR matures, this integrated design philosophy will likely become the norm—not just a best practice.

Historically, mass production and consumption have leaned into obsolescence, with products designed for short lifespans and frequent replacement. But EPR regulations are flipping that model. By making producers financially responsible for their products throughout the entire lifecycle, governments are pushing industries to think more holistically. The new goal: build things to endure, not expire.

Durability as a Design Standard

Durability is emerging as a defining characteristic of responsible product design, especially under modern EPR frameworks. Instead of optimizing for low-cost, short-lived goods, many producers are now focusing on creating products that can withstand regular use, environmental stress, and time itself. This pivot reflects a deeper understanding that product longevity plays a critical role in reducing the volume of waste entering the system.

Designing for durability starts with choosing materials that resist wear, corrosion, and fatigue. For example, shifting from plastic to metal casings in electronics not only improves resilience but also enhances recyclability. Similarly, using reinforced stitching and abrasion-resistant fabrics in apparel can significantly extend product lifespan. But material strength is only part of the equation. Engineering simplicity—fewer moving parts, modular construction, and robust joints—also helps reduce the risk of early failure.

Importantly, durable design must still consider usability and affordability. A long-lasting product that is prohibitively expensive or difficult to operate will fail in the market. The goal is to balance performance, longevity, and practicality. In doing so, producers not only reduce their environmental footprint but also improve customer satisfaction and brand reputation—an increasingly valuable asset in a world where consumers are prioritizing sustainability.

Designing for durability involves selecting robust materials, simplifying mechanical components, and stress-testing products for long-term use. For instance, in the electronics industry, some manufacturers are now opting for metal casings and modular internal components that can be easily repaired or upgraded. These choices not only extend a product’s usable life but also reduce total resource extraction and emissions over time.

Repairability and Modularity

A growing number of EPR frameworks globally are incorporating repairability indexes and rewarding companies that make it easy to replace parts. Think of laptops with tool-free access to batteries or appliances with downloadable repair manuals. Modularity—where parts can be swapped or upgraded without replacing the whole—plays a big role here, supporting a circular economy where waste is minimized by design.

Consumer Habits and Producer Incentives: A Two-Way Shift

The movement toward extended product lifespan is not solely being driven by regulation—consumer expectations are playing a powerful role. As awareness around environmental issues grows, buyers are increasingly questioning the throwaway culture of the past. There is a rising preference for quality over quantity, and consumers are more willing to invest in products that promise durability, repairability, and long-term support. This cultural shift is pushing producers to re-evaluate what value means in the context of design and delivery.

Simultaneously, Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) policies are strengthening the business case for longer-lasting products. When manufacturers are held responsible for the end-of-life collection and processing of their goods, producing items that last longer becomes financially beneficial. Fewer replacements mean fewer units returned or collected under EPR obligations, lowering overall compliance costs. Additionally, durable goods tend to be easier to refurbish, reuse, or remanufacture—further contributing to a circular economy model.

Many companies are now introducing durability as a core selling point, offering extended warranties, upgradeable components, and even lifetime service options. Some are adopting take-back schemes and resale platforms to reclaim and extend the life of their own products. These actions serve not only to comply with regulations but also to differentiate themselves in a competitive, eco-conscious marketplace.

- Consumers are favoring brands that offer transparency and long-term value.

- Producers can reduce EPR-related costs by investing in durable product design.

- Extended warranties and repair programs help build customer trust and loyalty.

This two-way shift between consumers and producers is creating a reinforcing loop. As consumers demand more durable, sustainable products, companies innovate to meet those expectations. In turn, these innovations further normalize long-lasting design and responsible consumption. The more this cycle continues, the closer we move toward a sustainable system where economic and environmental interests are aligned. Ultimately, the success of EPR lies not only in policy enforcement but in this collaborative momentum toward smarter, more resilient products.

While policy nudges producers toward more sustainable design, consumers are also becoming more aware of longevity and total cost of ownership. This behavioral shift complements EPR’s goals by generating demand for products that are not only greener but also more reliable and cost-effective over time.

How EPR Encourages Sustainable Business Models

Under EPR schemes, producers can earn credits or avoid penalties by extending the useful life of their products. Some companies have even adopted leasing or product-as-a-service models, where they retain ownership and responsibility for maintenance and eventual recovery. This business shift aligns financial incentives with environmental stewardship, creating a win-win for companies and the planet.

- Durability reduces waste at the source, not just the end

- Repairability builds customer trust and brand loyalty

- EPR ties environmental outcomes to product design decisions

Global Trends: How EPR Is Redefining Design Across Sectors

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) is no longer a fringe concept—it’s becoming a global design directive that is reshaping how industries approach product development, sustainability, and compliance. Across continents, governments are implementing EPR regulations that not only mandate post-consumer waste management but also influence what happens much earlier in the value chain: design. As a result, producers in sectors ranging from electronics to textiles to packaging are being pushed to adopt principles that prioritize longevity, reusability, and ease of recycling.

In the European Union, for instance, the Ecodesign Directive and Circular Economy Action Plan are encouraging manufacturers to create products that last longer, are easier to repair, and have parts that can be recovered and reused. France has gone further by introducing a repairability index that must be displayed at the point of sale for certain electronic devices. This index rates how easy it is to repair a product—information that influences consumer choice and motivates producers to score higher.

In India, the e-waste and plastic waste management rules under the EPR framework have begun to impact upstream processes. Producers are expected not only to meet collection and recycling targets but also to reduce the generation of waste at source. This has sparked new conversations around using recyclable materials, phasing out difficult-to-recycle components, and designing products that can survive multiple life cycles. Companies that fail to adapt may face higher costs and risk regulatory penalties.

Textile and fashion industries are also undergoing transformation. In countries like Sweden and the Netherlands, policies are emerging that hold clothing brands responsible for end-of-life garment recovery. These measures are prompting a shift toward more robust, timeless apparel design—clothes that are less trend-driven and more repair-friendly. Similarly, packaging industries in countries like South Korea and Canada are seeing a rise in reusable and standardized packaging systems to minimize single-use waste.

- The EU is integrating durability and repairability into legal product standards.

- India’s EPR mandates are driving design-level changes in electronics and plastics.

- Apparel and packaging industries in Europe and Asia are embracing reusable, long-life solutions.

These international developments reveal a clear trend: EPR is no longer just about managing waste—it’s about designing it out of the system entirely. Companies that anticipate and align with these evolving regulations can unlock long-term value through sustainable design, while those that lag may find themselves left behind in an increasingly circular global economy.

From the EU’s Ecodesign Directive to India’s e-waste rules, EPR is being embedded into product policy frameworks worldwide. Manufacturers in electronics, appliances, and even textiles are being asked to prove not just compliance, but commitment—to make products that are safer, longer-lasting, and easier to recover or reuse.

Case Studies in Extended Lifespan Design

Several electronics brands have responded to EPR policies by reengineering their flagship products. For example, some smartphones now feature longer battery life and software support for 5+ years. In the appliance sector, companies are offering extended warranties and in-house repair services as a competitive edge. These cases show how durability can be both a regulatory requirement and a market advantage.

Design for Impact: The Future of EPR Is Built to Last

As the global shift toward sustainability accelerates, Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) is evolving into more than just a compliance mechanism—it’s becoming a blueprint for impactful product design. At the heart of this evolution lies a powerful principle: designing for longevity. Rather than focusing solely on post-consumer waste recovery, the future of EPR centers around preventing waste from being generated in the first place. That means creating products that are built to last, easy to repair, and capable of being repurposed or recycled at the end of a long, useful life.

This forward-looking model doesn’t just reduce environmental pressure; it also creates opportunities for innovation, brand differentiation, and customer loyalty. Companies that embrace ‘design for impact’ strategies are often able to cut lifecycle costs, streamline their supply chains, and respond more flexibly to changing regulations. Durable design also aligns with growing consumer demand for value and sustainability, especially in markets where awareness of environmental issues is high.

For EPR frameworks to be truly effective in the long run, they must reward thoughtful design. This includes incentivizing producers who go beyond minimum compliance—those who build products that are modular, upgradeable, and resource-efficient. As more countries update their EPR rules to reflect these priorities, producers who lead with sustainable design will gain both regulatory and market advantages.

- Designing for durability reduces material and energy consumption over a product’s lifecycle.

- Modular and repairable products support service-based business models and job creation.

- Anticipating EPR policy trends can lead to early compliance and long-term cost savings.

Looking ahead, the role of EPR will continue to expand—from a tool for managing waste to a catalyst for reimagining how we design, use, and value the products in our lives. The most resilient businesses will be those that see durability not as an added cost, but as a strategic investment in the future. Building for impact means building to last—and that’s a future worth designing for.

As EPR policies continue to evolve, durability and extended lifespan will become central pillars in the design process. Rather than seeing EPR as a burden, forward-looking manufacturers are embracing it as a catalyst for innovation, value creation, and environmental impact. Building for longevity isn’t just good policy—it’s good business. In the coming years, the most successful products won’t be those that sell the fastest, but those that serve the longest.

Leave a Reply